Top Story

New ULI Boston Report: Lack of Options for Middle-Income Households Jeopardizes Growth

September 28, 2016

By Mike Hoban

The Boston metropolitan area is experiencing a shortage of housing that is affordable to middle-income households—a deficit that threatens the region’s ability to attract and retain a sufficient workforce and continue on a path of robust economic growth. Those are the major findings of Building for the Middle: Housing Greater Boston’s Workforce, a report recently published by the ULI Boston/New England Housing and Economic Development Council. The report’s findings were discussed this month by a panel of housing experts convened by ULI Boston.

Over the past two decades, Boston’s middle-income population has been shrinking steadily while upper- and lower-income populations have grown, shifting the balance among these groups, according to Building for the Middle.

Building for the Middle examines dwindling housing and occupational choices for middle-income households.

Between 1990 and 2014, the number of middle-income households declined by 2 percent, while the number of high-income households rose by 33 percent and lower-income households by 40 percent. More than half the growth in the lower-income population can be attributed to extremely low-income households. Middle-income is defined in the report as households earning more than 80 percent but less than 120 percent of area median income. For a middle-income family of four in Greater Boston, household earnings range from $68,000 to $113,000.

“The middle class is being squeezed out of the market,” said panelist Karen Kelleher, deputy director for MassHousing, an independent, quasi-public agency that provides financing for affordable housing in Massachusetts. “This report confirms for us things that we’ve seen from other studies that have been done, but really takes it to another level of trying to understand how the workforce is changing as opposed to just what’s happening in the housing market.”

The report notes that the decline of occupations aimed at middle-income earners has hollowed out the middle class. The number of office, administrative, and maintenance jobs has declined, while low-wage jobs in sales and food preparation have increased in number, as have high-wage positions in management, health care, and technology-related fields.

“When we talk about wage polarization in America, this is what’s happening,” said panelist Tim Reardon, data services director for the Metropolitan Area Planning Council, the regional planning agency that provided data analysis for the report. “We are growing the number of working households who are low- and high-income while we are losing the middle.”

The report is the result of an extensive research effort led by the ULI Boston housing and economic development council, cochaired by Travis D’Amato, managing director at JLL, and Mathieu Zahler, senior project manager at Trinity Financial.

Building for the Middle explains that 36 percent of Greater Boston’s middle-income households are cost-burdened, spending more than one-third of their income on rent, mortgage, or other home-related payments. Rising housing costs have hit middle-income homeowners in Boston and inner-ring suburbs particularly hard: the number of these households considered cost-burdened increased by 27 percentage points from 1990 to 2014.

Further exacerbating the problem is a scarcity throughout the region of both for-sale and rental units that are affordable. In Greater Boston, only 22 percent of single-family homes and 39 percent of condominiums are affordable to a household of four earning $75,000 per year. Only 12 percent of two-bedroom rental units in the region are affordable for that same household.

Those percentages decline further—to 10 percent or less—for both homeownership and rental units in more than three dozen of the region’s exclusive suburban communities, according to the report. Affordable opportunities do exist in some “gateway cities” such as Lynn, Brockton, Lawrence, Lowell, Chelsea, and Revere, but many of those communities still need significant investment to improve the overall quality of life needed to entice middle-income households. “There are pockets of opportunity, but not necessarily where middle-income folks feel like they want to live right now,” Reardon said.

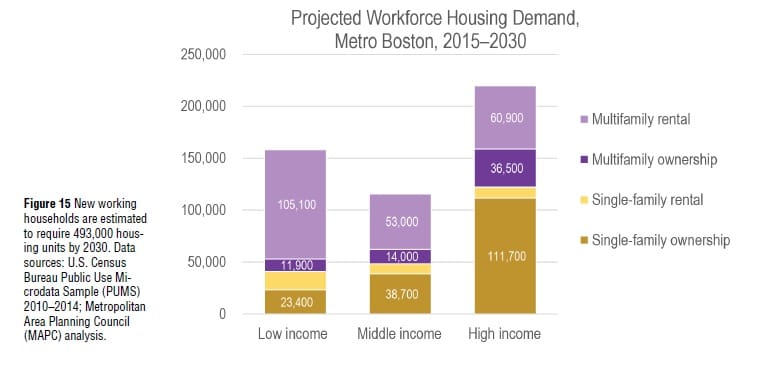

With the baby boomers now retiring, it is anticipated that 717,000 workers born between 1945 and 1970 will leave the Greater Boston workforce by 2030. In order for the region to maintain its current rate of employment growth—about 4 percent—it will need to add more than 800,000 new workers to replace those who will retire, according to Building for the Middle. To accommodate these new workers, at least 200,000 additional housing units will need to be built in Greater Boston, including 21,000 units priced for middle-income households and 108,000 units priced for low-income households.

The bulk of that housing will have to come through multifamily development, but the vast majority of cities and towns in Massachusetts have historically restricted dense development. High development costs related to land acquisition, permitting, and construction are choking new housing supply as well.

To ease those pressures on middle-income households, the report recommends that local and state policy makers increase the amount of housing affordable to middle-income households in wealthier suburbs, make gateway cities more appealing to those households, and increase housing production affordable for households of all income levels.

“Across the country, we have a huge and growing shortage of housing,” said panelist Stockton Williams, executive director for the ULI Terwilliger Center for Housing. “We’re not building nearly enough at any price point—except at the high end, and it really is having a trickle-down effect that is exacerbating rent growth and home price pressure that is hitting folks in the middle and lower end especially hard.”

By 2030, nearly 500,000 new housing units will be required for workers across income levels for Boston’s growing economy.

Mike Hoban is a Boston-based writer who covers the commercial real estate industry.